Overview

What is a SLAP TEAR?

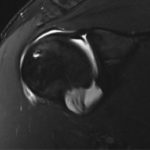

- The labrum is a fibrocartilage tissue encircling the glenoid between the hyaline cartilage of the joint surface and capsule.

- The labrum improves glenohumeral (GH) joint static stability by resisting humeral head translation, enhancing joint concavity, and increasing the glenoid depth.

- The superior labrum is also intimately associated with the origin of the long head of the biceps which may offer dynamic stability to the GH joint.

Classification

- SLAP tears are classified into four types in 1990

- Type I lesions involve fraying and degeneration of the superior labrum

- Type II lesions involve detachment of the biceps anchor from the glenoid

- Type III and IV lesions consist of a bucket-handle tear with type IV tears extending into the biceps.

Why do throwers get SLAP tears?

- The throwing shoulder when compared to the non-dominant shoulder demonstrates increased passive external rotation (ER), decreased passive internal rotation (IR), increased humeral retroversion, anterior capsular laxity, and posterior capsular contracture

- These adaptive changes are the result of the rapid, high-energy stresses placed on the upper extremity during repetitive throwing particularly during adolescent age. Such alterations allow for efficient energy transfer and increased throwing velocity, but can also create a disposition towards instability and pain.

- Internal impingement is the contact of the posterior supraspinatus and infraspinatus against the greater tuberosity and posterior-superior aspect of the labrum with the arm in abduction and ER. While physiologic contact between the posterior-superior labrum and rotator cuff occurs in asymptomatic individuals during the activities of daily living, repetitive high energy motion causes changes, including partial thickness rotator cuff and SLAP tears.

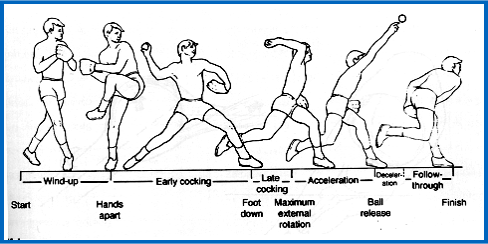

- During the deceleration and follow through phases of throwing, the posterior capsule withstands tensile forces up to 750N. Shear forces across the GH joint, permits internal impingement, and allows anterior humeral head translation leading to instability. Furthermore, the hyper-abducted and maximally ER shoulder forces the biceps posteriorly and twists it about its anchor on the glenoid. This places a torsional force on the posterior superior labrum which Burkhart described as the peel-back phenomenon.

How is SLAP Tear Diagnosis Made?

Symptoms

- Throwers with SLAP tears may experience initial symptoms of decreased control, velocity and difficulty warming up. Often symptoms develop insidiously and gradually.

- Patients with SLAP tears may report anterior-superior or posterior-superior pain exacerbated by overhead activities and/or mechanical symptoms of popping, catching or locking. These symptoms most often occur during the late cocking phase consistent with internal impingement. Patients may also have rotator cuff pathology leading to complaints of a “dead arm” or shoulder weakness after throwing, or instability such that their shoulder feels as if it is “slipping out” while throwing.

Treatment Options

Non-operative Treatment

- The mainstay of non-operative treatment for SLAP tears is reducing inflammation, restoring normal glenohumeral and scapulothoracic motion, and optimizing rotator cuff and peri-scapular muscle strength. In addition, the kinetic chain is optimized and core strength is improved. Initially treatment includes a period of rest, posterior capsular stretching, and restoration of normal scapular and glenohumeral strength and stability to improve any dysfunctional shoulder mechanics. This can be supplemented with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy or intra-articular cortisone injections. Posterior inferior capsular stretches include the sleeper stretch and cross-body adduction stretches and can be successful in approximately 90% of athletes with associated GIRD.

- Ahmad and his team examined the role of non-operative treatment in 39 patients with known SLAP tears. Nineteen patients (49%) did not require surgical treatment, and 71% of these patients returned to the same or better levels of participation in sports after a regimen consisting of NSAIDs, scapular stabilization exercises, and posterior capsular stretching. A lower rate of return to sport (67%) was identified in overhead athletes.

Operative Treatment

- General goals for operative SLAP treatment include stabilization of the biceps anchor, debridement of degenerative labrum and stabilization of remaining healthy labral tissue.

- More specifically, type I and III SLAP lesions are treated with debridement and resection of the unstable bucket-handle tear, respectively. Type II SLAP lesions require repair and

- Type IV lesions are treated with repair depending on the severity of biceps tendon involvement. Debridement alone of unstable SLAP tears (types II and IV) have been associated with poor long-term outcomes.

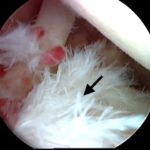

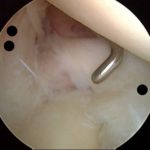

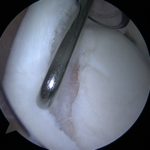

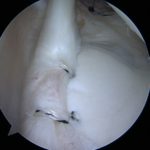

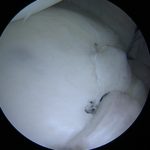

- The surgical repair of SLAP lesions has evolved with advances in arthroscopic instrumentation and techniques. The most current recommendations are for repair with suture anchors. Figures 3A-3D show intraoperative photos of a type II SLAP tear repair in an elite baseball pitcher using a minimally invasive, percutaneous technique with knotless suture anchors.

- We prefer percutaneous anchor placement to minimize rotator cuff morbidity associated with the creation of a large cannula in a lateral Wilmington Portal. Preventing rotator cuff morbidity should be considered paramount in overhead athletes who place a high demand on the rotator cuff and may already have cuff pathology due to internal impingement. An additional advantage of not working through a cannula is that the surgeon has a greater degree of freedom for placement of suture anchors. We also prefer to use knotless suture anchors for SLAP repairs as this may minimize chondral surface abrading from prominent suture material.

What is SLAP Repair Rehabilitation?

- Post-operatively, patients are placed in a sling for 4 weeks with immediate ROM exercises for the elbow, wrist and hand. Physical therapy with passive and active assisted shoulder ROM are initiated 2 weeks postoperatively, with rotator cuff, deltoid, peri-scapular strengthening gradually introduced to regain full ROM by 6 weeks post-operatively. The biceps is more closely protected, with strengthening occurring 8 weeks out from surgery.

- Throwing is permitted at 4 months through an interval throwing program that commences with throwing on a level surface. Throwers continue a strengthening and stretching program during this time with emphasis on posteroinferior capsular stretching. At approximately 9 months pitchers begin throwing from the mound.