Each spring, the Columbia University Varsity “C” Dinner celebrates the success and achievements of the 700+ CU athletes who grind in their sports and grind with the added responsibility of Columbia University’s huge academic demands.

2020 marks my 30th-year reunion and this spring I find myself reminiscing of my own experiencing at Varsity “C” Dinners. The soccer team always sat close to the lectern back then. Seniors took seats with the best view, and the freshman took the final empty seats. We were close enough to hear speakers directly and not through the PA system echoing to the back of the room. We speculated that the more successful your team, the closer your table was positioned to center stage. And yes, the fencing team was consistently positioned between soccer and center stage — even back then!

Last week, I had the great fortune of attending the 99th Annual Varsity “C” Celebration as an alum. I felt supportive of the CU varsity athletes while relaxing in my bed wearing running shorts and an Under Armour sweatshirt. The COVID-19 pandemic had forced CU to reinvent the end-of-year athletics banquet as the “Virtual C” Celebration, and it was to be streamed live on Columbia Athletics YouTube channel.

The challenge of converting in-person social celebrations to online events has been faced by all universities and high schools this year. Text messages were flying amongst my soccer alumni buddies encouraging full attendance of the Virtual “C” celebration, and also the upcoming weekend of alumni reunion festivities. I sipped a glass of wine with my wife Beth Shubin Stein — ‘91CC. We shut down our outlook inboxes and received direct screen eye contact with Dean Kowalski ‘13CC. Dean is a Columbia men’s basketball alum and master of Virtual “C” ceremonies that evening. He was squinting in bright sunlight, wearing a well-fitting tuxedo, and demonstrating a comfortable mature screen presence stemming from his celebrity experience on CBS’s Survivor: Island of the Idols. The second-place Survivor finisher shot off satire saturated introductions of CU leaders that blended nicely with the leadership gratitude speeches.

Unexpected special guests periodically surprised the streaming audience throughout the production, bringing a sense of honor and pride. 23-time Grand Slam tennis champion Serena Williams, Jim Nantz of CBS Sports, musical artist MC Hammer, and NFL wide receiver Golden Tate of the New York Giants all had some time on the virtual stage. New York Yankees manager Aaron Boone also jumped on to send special CU congratulatory remarks.

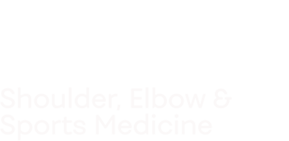

Between speeches, various highlight sizzle-reels of the 2019–20 varsity sports season kept popping up, with final second goal-scoring action, huge comebacks, blocks, dunks, and swim records being broken. The event had the professional touch of ESPN highlights being shown at the Oscars. The Karen Blank Award went to Anne Cebula. This great honor goes to a Barnard athlete who exemplifies academic success, athletic achievement, strong sporting behavior, and community commitment. Cebula was the first-ever NCAA Individual Epee Champion from Barnard. Cebula got me thinking of my 8th floor McBain dorm room neighbor, Katy Bilodeau. Katy was a four-time All-American, four-time Northeast Regional champion, and four-time All-Ivy League selection. In both 1985 and 1987, she won the NCAA women’s foil titles, becoming the first woman ever to capture two NCAA fencing crowns. She was humble and soft-spoken, but would “flip the switch” for competition. She lived across the hall from me and was the top-ranked women’s foil fencer in the United States from 1985 to 1992. She was later named the NCAA Athlete of the Decade for the ‘80s! Katy and this year’s impressive Anne Cebula are model Columbia blue champions in a long lineage of fencing success at Columbia.

Game of the Year…

New to the Varsity “C” Dinner this year, Columbia recognized the top games and plays of the year, with a social media vote deciding the winner. Football’s Columbia vs Harvard game at home was nominated and while I was watching, it had winner written all over it. A score of 10 to 10 forced overtime, setting up Columbia to strike with a touchdown that beats Harvard for the first time since 2003. Amazing! The final score was 10–17.

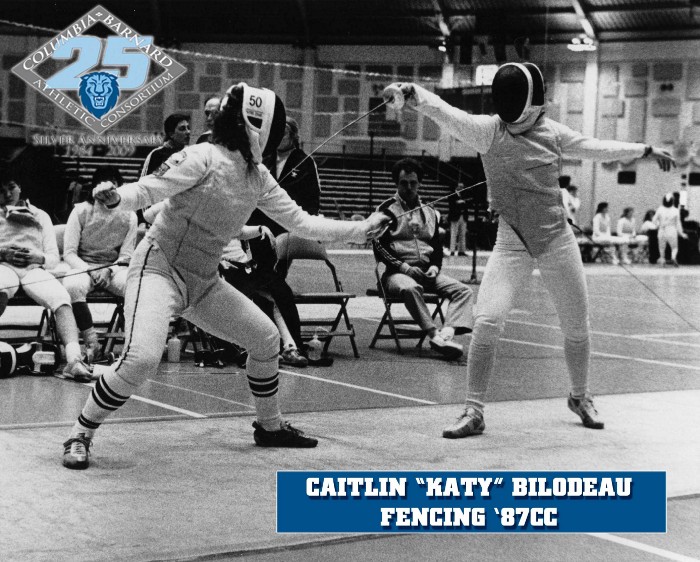

Did football have any reason to celebrate at the varsity “C” dinner during my time? Well, they suffered the longest losing streak in the history of college football on October 8, 1988. 44 games lost over a span of nearly five years. It was finally broken by defeating Princeton 16–13 when Columbia’s Greg Abbruzzese rushed for 182 yards as the Lions won for the first time in 47 games (ties included). I was there, in the stands, trying to get over the frustration of our devastating soccer loss to Princeton that had finished just prior to the football game that day. Columbia fans stormed the field, tore down both goalposts, and frolicked in the cold and damp.

Today, I remain close friends with Greg Abbruzzese, and when we are together to this day we talk about all things Columbia sports, past & present. I recently asked him what he remembers most about that special day on October 8th, 1988. “Don’t you mean October 7th” was his emphatic reply. Abba and essentially the entire football team broke their 8 pm curfew that night to compete in a lip-synch contest that was held in the Plex. Among other competitors, soccer goalkeeper Jeff Micheli did a solo number, a group of cheerleaders sang “Bust a Move”, one of which would later become Abba’s wife, and the football players came in first with “Candy Girl” by New Edition. As far as October 8th goes, Abba told me his greatest emotion with the win was not for himself but instead for his senior teammates, crying their hearts out as they witnessed the transfer of bright yellow goal posts from 218th street, all the way down to 116th street. Abba is a true Columbia Blue champion.

As the Virtual “C” Celebration progressed, Men’s Soccer got it’s own Virtual “C” spotlight nomination for game of the year with a 3–2 victory at UConn. Senior John Denis bent a direct free-kick into the upper right corner in the 15th minute to open the scoring. Dennis then assisted a go-ahead goal by first-year Uri Zeitz in the 62nd minute. UConn had equalized in the second half, but three minutes later, Denis answered a final time with a tremendous goal in the 84th minute. On a cross driven by Sebastian Gunbeyi, Denis timed his run and flicked a header to the right corner netting. This was a spectacular game combining excellent tactical play with gritty teamwork that is the signature of Head Coach Kevin Anderson. And it edged out the other nominees for the 2019–20 Columbia University Varsity C Game of the Year!

I embraced the achievements of Men’s Soccer and experienced subtle thrills with their goal-scoring highlights that long ago I once felt myself, at Baker Field. I remember training all summer to prepare for preseason before moving into an almost empty McBain in the last week of August, with only a handful of students on campus. I remember driving the old dark blue vans on the winding west side highway to and from Baker Field for the grueling 2-a-day practice sessions. Looking back, we should have never raced the 2 vans on the winding highway, but I always enjoyed the empowering feeling of parking them on college walk when we got back to campus. I would park with the passenger exit in contact with college walk shrubs, forcing the other players to scrape the brown branches while exiting the sliding van door. From game 1 until the last home game of the season, tradition had us pat the lion statue outside of Chrystie field house. That patting of the lion served as each player’s catalyst to enter game-time mode, as they jogged steadily onto the pitch. Early season wins seemed easy. The struggle would typically begin with the first set of midterms. Lack of sleep, academic anxiety, and body parts that were constantly sore. 17 engineering credits and cold weather weighed in heavily when games mattered most.

As a Columbia University Orthopedic Resident Physician…

At my own CU graduation, my dream was to stay closely connected to CU sports and serve the game of soccer that I love so much. As a physician, I could preserve the dreams of athletes jeopardized by injury. Just a few short years after my graduation, my dream was alive as an orthopedic surgery resident at my very own Columbia University! My blue scrubs were the same color as my Columbia blue jersey. In the Fall I purposefully designed my rotations to be at Allen Pavilion Hospital, the building adjacent to the soccer stadium. That way I could sneak out and watch CU matches from time to time. Many of the hospital units directly faced the stadium. In fact, the inpatient units were named either “Field” East or “Field” West. Orthopedic patients were on 2 Field West. One evening in the Allen ER, I finished reducing and casting the radius of a patient who suffered a displaced fracture. After sending her for repeat x-rays to check the bone alignment, I walked outside to the pitch during pregame warmups and said my hello’s to Dieter Ficken the Head Coach at the time, and my former teammate Kurt Dasbach who was the assistant. The plaster on my scrubs made it clear I was working and that I could not stay long. On weekend calls at the hospital, I would do the same runs in Inwood park that we did in preseason soccer training. Except this time carrying a pager, making sure to never wander off more than a few minutes running distance back to the hospital.

How Athletics Shaped my Career….

Like all Columbia students, I decided to attend Columbia for very specific reasons. The opportunity to join a team consistently ranked in the Division I top 20 every year, a second-place finish in the Division 1 NCAA finals in ’83, combined with an incredible engineering educational opportunity. The privilege came with pressure. All athletes seek the highest level of performance which demands a complex interplay between mind and body. This includes strength and stamina complemented by years of skill training, heightened focus, split-second decision-making, and calm confidence. Athletes are judged on their qualities as a supportive and inspiring teammate and we all value the gritty player who learns from failure and leaves it all on the field. The characteristics of CU athletes are entirely the desired characteristics of surgeons.

COVID-19 Knock Down…

Peter Pilling the CU Athletic Director, appeared on the Varsity “C” Virtual meeting and made special mention to the issues of coronavirus. Coronavirus has not only taken lives numbering greater than 100,000 in the US, not to mention 30,000 in New York alone, but it has also taken experiences away from our students and student-athletes. Social distancing mandates shut down Columbia classes. Spring sports were canceled. Baseball players as an example were denied the opportunity to compete this spring. For many athletes, COVID-19 killed the final season of their competitive career. I also know this devastating feeling first hand. I lost my senior year to an MCL knee injury. The first game of the season against Harvard, in the first half, I delicately snuck inside an attacking forward (I still remember his name) positioning myself between him and the ball. I pushed the ball out of his control and into my control. While steering the ball with my right foot, my planted left leg suddenly felt a crack. I was knocked to the ground. My frustrated opponent had drilled the outside of my planted knee causing my MCL to rip. I lay on the ground while Felix gave the crimson player a yellow card. Felix was the ref, back then we knew most officials by their first name.

Injuries knock individual athletes down. The 2020 pandemic knocked entire teams of athletes down. While I appreciate the common university commencement message “follow your passion,” my CU athletic experience shaped my philosophy somewhat differently. It is simple. Get up when you get knocked down. That’s what successful athletes do. That’s what successful people do.

What was missing from the Varsity “C” virtual celebration?

“Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising each time we fall”

— Confucius

The Virtual “C’ Dinner had a palpable absence of live social gatherings which is obviously impossible to reproduce on a computer screen. I remember at my last Varsity “C” Dinner, I was greeting friends from other sports that I rode the bus with day after day, listening intently as they spoke about the next steps in their career or advancing education. Still, the Virtual “C” Dinner was consistent with prior Varsity “C” Dinners in that it celebrated achievement after achievement. The Virtual “C” Dinner started with awards to the highest cumulative GPA’s for varsity athletes. Can you believe 67 athletes maintained perfect 4.0’s? Then came awards for best this, and best that. What has always been missing? — the failures. There was no footage of the near misses. Those are the plays and games that I think about regularly, much more than the wins 30 years later.

So let’s be careful of the message we craft for graduating students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each athlete had to overcome incredible obstacles to get to their collegiate level of competition. And those that broke records or those who rose to convert a loss to a win in the final seconds probably overcame even more difficult obstacles. Michael Jordan publicly embraced failure and stated “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots. I’ve lost almost 300 games, and 26 times, I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed.” This embrace of failure is a testament to the positive mindset. A positive growth mindset believes that properly applied effort leads to achievement. I hit an obstacle as a freshman. I became intimidated by the senior more skillful players, such as the talented Neil Banks. Ivy League Rookie of the Year, Ivy League Player of the Year, and All American “ Banksy” somehow could smell insecurity and had ZERO tolerance for players who could not execute. I began to avoid getting free to receive the ball during training. I lost the enjoyment of playing. I became keenly aware that the competition I was with and the quality of players were some of the highest in my career. “Banksy” lived on the 8th floor of McBain. At night he would knock on my door to play Nerf basketball with a hoop he hung up over his outer door. I enjoyed one-on-one Nerf basketball with him despite his exuberant celebrations and his 6-inch height advantage. I enjoyed it even though he destroyed me. So why would I also not enjoy playing the game I loved, the game I was really good at? Like a switch, I converted fear into the joy of simply playing. Why wouldn’t I want the ball every time I could get it to show what I could do and enjoy playing like when I was a kid in the backyard? Why not embrace the opportunity? Why fear failure? Banksy taught me a valuable lesson.

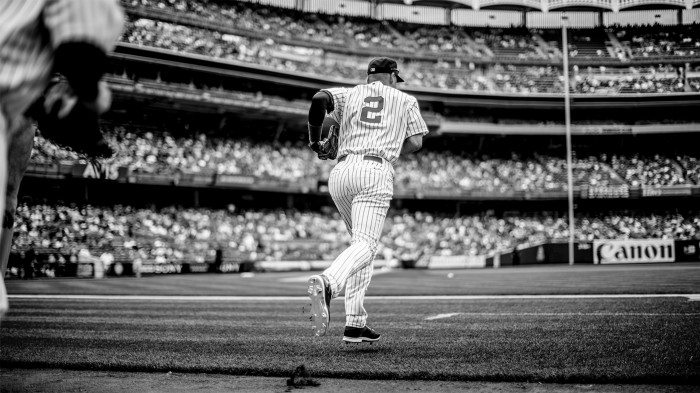

Several years ago while in Yankee Stadium serving as the team’s Head Physician, I watched Derek Jeter talking to a few teammates who were slumping. Jeter told them to simply go to the plate, forget about the critical fans and reporters, have fun, and stop worrying about failure. In fact, in Jeter’s post-game interview on the last home game of his career, he stated he was wishing the ball would not be hit to him at shortstop. How incredible is that? Perhaps the best shortstop in the history of baseball did not want the ball to be hit to him on his last game. This was in response to the intense emotion he was feeling. The game unfolded with him getting a walk-off hit to win the game — September 25, 2014. Despite the emotion of a career-ending game, he clearly managed his last game by taking his own advice, avoiding the fear of failure, and concentrating on the opportunity — and also to just have fun!

Columbia Strong

How did my Columbia soccer experience shape my career? I learned valuable traits as a player that some skilled surgeons possess. Surgeons must maintain a positive mindset, accept the possibility of failure, lose the fear of failure when operating, and celebrate success. Surgeons must embrace failure and learn from every mistake as opposed to feeling that a failure has defined them.

Columbia’s education is well-known globally amongst all institutions for its Core Curriculum that emphasizes the classics. I took the mandatory Lit Hum as a mechanical engineering student. At the time it was a chore. However, classical literature and philosophy have further shaped my current methods of dealing with hardship to this day, and I have come to admire and subscribe to Stoic philosophy.

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

— Marcus Aurelius

Aurelius, the second-century Roman emperor, practiced Stoicism which argues that individuals shape their destinies by controlling what they can and letting go of what they cannot. The Stoics believe the essence of life is how we consciously choose to respond to the things that happen to us. Aurelius puts it as standing at a wall of opposition that is intimidating, but the wall also creates motivation. Knowing the wall you have to climb can push you to find a way over it.

Conflict is uncomfortable, stressful, and scary. However, if you can embrace the conflict that stands before you, accept the problem and challenge it, you can find the way that you didn’t know was there. George Washington embraced Stoicism. Athletes and surgeons today embrace Stoicism because they understand their oppositional and internal conflict.

Today, Stoicism is embraced by nearly every professional sport — including some of the most renowned football coaches and executives in the world like Bill Belichick, Nick Saban, Michael Lombardi, Pete Carroll, and many others. I received a copy of “The Obstacle is the Way” when Ryan Holliday sent boxes of them to the New York Yankees. He ignited the connection between sports and Stoicism. Stoicism is not a set of ethics or principles. It’s a collection of thought exercises designed to help people through the difficulty of life. To focus on managing emotion; specifically, non-helpful emotion.

“Some things are within our power, while others are not. Within our power are opinion, motivation, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever is of our own doing; not within our power are our body, our property, reputation, office, and, in a word, whatever is not of our own doing.”

— Epictetus, Early Stoic

Stoics focus on things within their control. They ask themselves; Is it within my control? Can I do something about it? Am I able to change anything? If something isn’t within your control, or you don’t want to change anything, accept reality, and move on.

How I Decided on my Career…

Like all athletes, I never wanted my soccer career to end. Realizing my career would at some point come to a close, especially after my knee injury as a senior, I decided I would serve soccer players and all athletes of every level of play as a sports medicine physician. My soccer experience at Columbia confirmed my decision to become a surgeon and gave me the foundation to succeed as a surgeon. Athletes get knocked down. Sometimes by injury, sometimes by coaches, sometimes by self-doubt, and in the spring of 2020 by a pandemic caused by a virus! Athletes also know how to get back up and to lead by example.

Operating Last Friday…

Last Friday I operated at the Allen Pavilion. My usual operating rooms at the Milstein hospital were reconfigured to take care of COVID-19 patients. The Allen hospital was where, as a freshman, I would retrieve soccer balls from its parking lot that got kicked over the stadium fence. It was where, as a resident, I would take quick breaks and watch matches in the fall. On this particular Friday, just before walking through the hospital entrance, I stood for a moment. It was 6:30 am and I had a mask on. The soccer field still had the bubble up. Why? — it was now a field hospital in case the pandemic surged above our hospital’s capacity. As I walked into the hospital changing room, resembling a Chrystie Field House locker room, I mentally reviewed surgical plans. My first patient had a torn and retracted triceps tendon that needed surgical reattachment. My second patient was a collegiate baseball player with loose chips in his elbow causing it to lock. My third patient was a high school wrestler who tried to gut out a state championship with an unstable MCL. The same injury I sustained as a senior at CU. The fourth patient, a Jiu-jitsu competitor, separated his shoulder and tore his rotator cuff. He had constant pain and inability to lift his arm since the injury. At that moment, I was right where I wanted to be — getting athletes back to health.

While the tradition of the Varsity “C” whether live or virtual celebrates individual achievements, games won and records broken, the real achievements are in those athletes who overcame obstacles. This year every athlete experienced the obstacle of the coronavirus. The pandemic will act like an open wound. It will take time to heal. There will be a scar. For many, the scar will remain ugly to them. For some, the scar will be a symbol of their most challenging time, a reminder to feel gratitude when the world returns to normal, and proof that obstacles can be overcome. To all the Columbia graduating varsity athletes and all students who have been knocked down, I wish to congratulate them on getting back up.

Anyone who wore a Lions Uniform, before or during the Coronavirus pandemic, knows what it is to Bleed Columbia Blue.